Headlines!

Unfolding 117 Years of History with the Miami Herald

Online Exhibition

Curatorial Statement

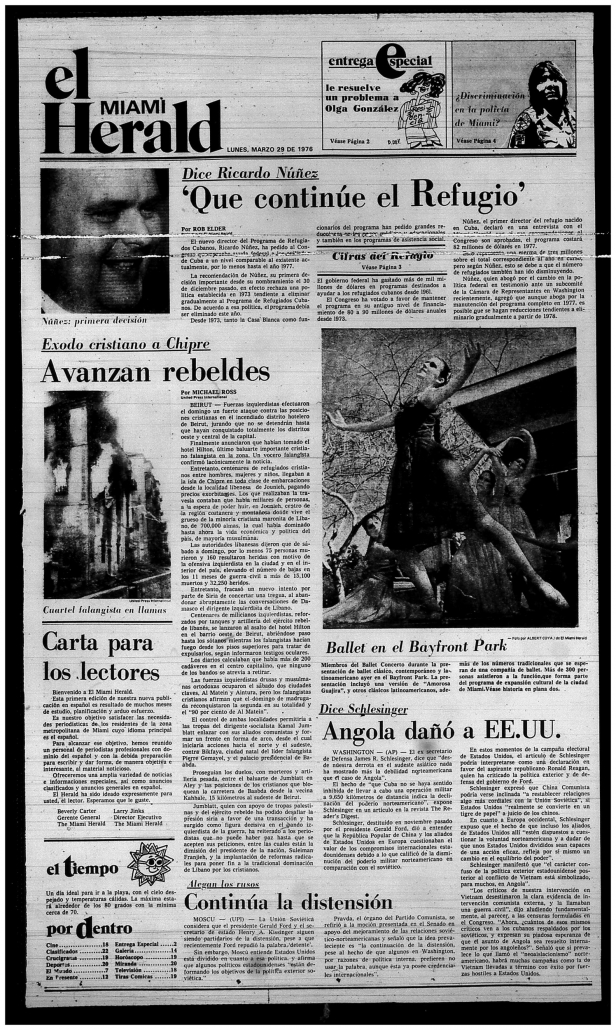

Since the City of Miami’s founding in 1896, newspapers have played an unparalleled role in shaping public opinion, solidifying a sense of community, and reporting the events which have shaped the course of history. The newspaper – which dates back to 17th century Europe – often serves as a society’s collective consciousness; a battleground laden with conflicting ideologies, explorative creativity, and reflections of the self. Headlines! Unfolding 117 Years of History with the Miami Herald serves not only as an unfolding of the Miami Herald’s past, but also of city’s past, for the identity of both the newspaper and Miami are inseparably intertwined.

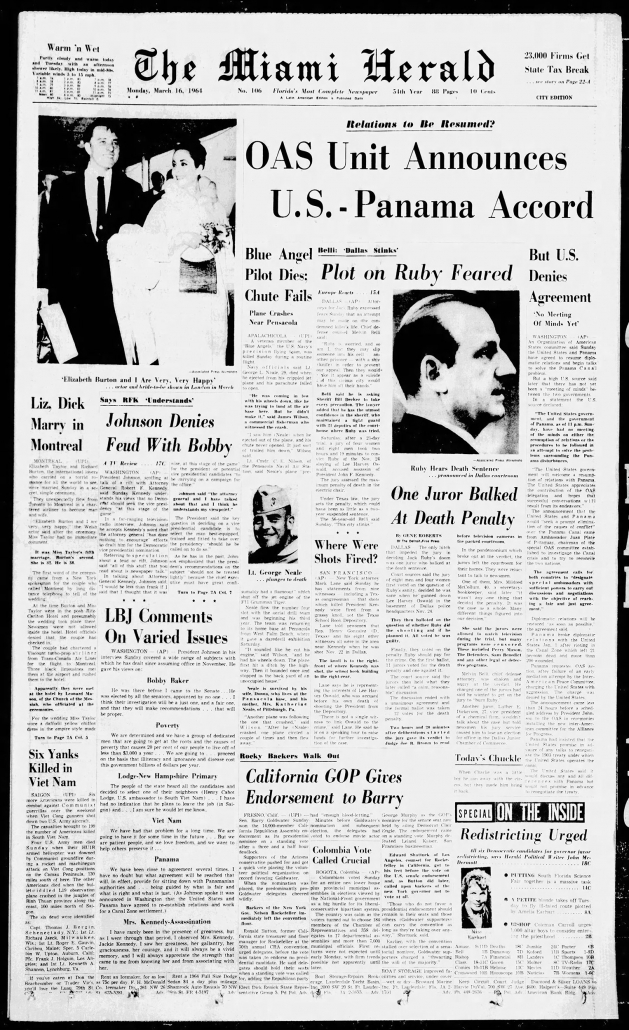

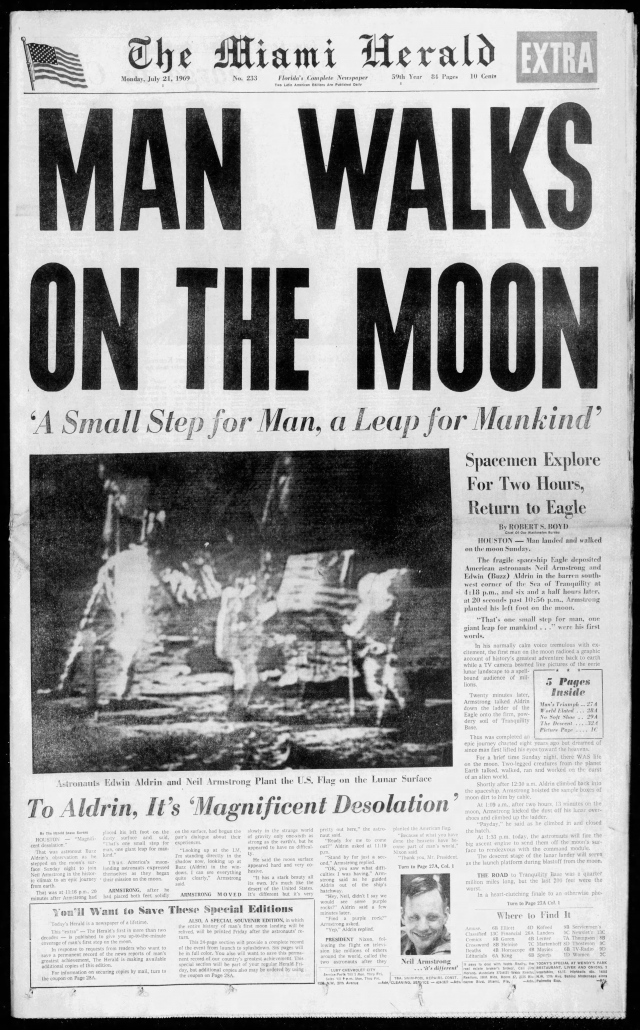

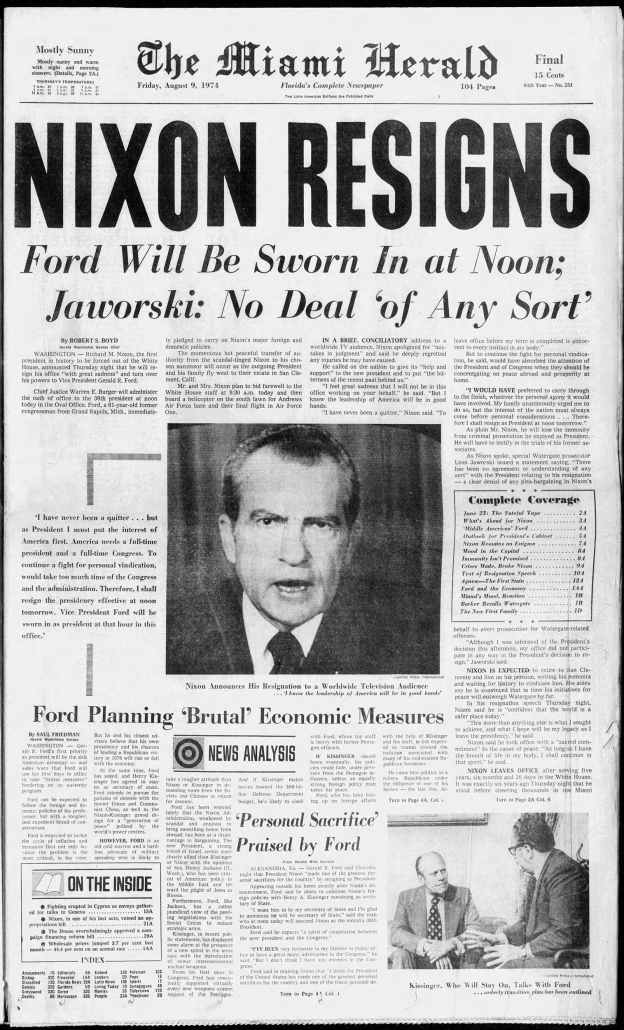

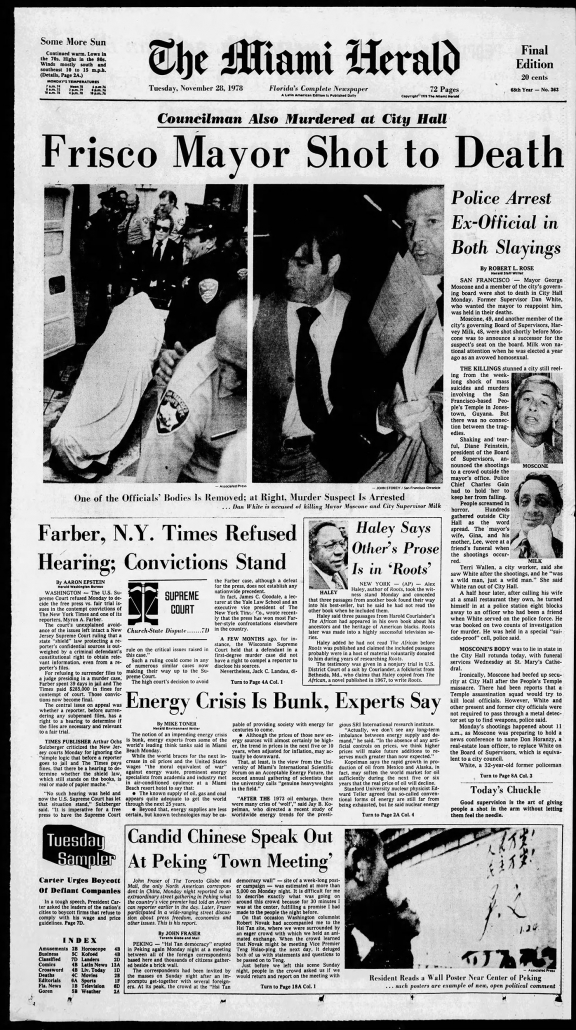

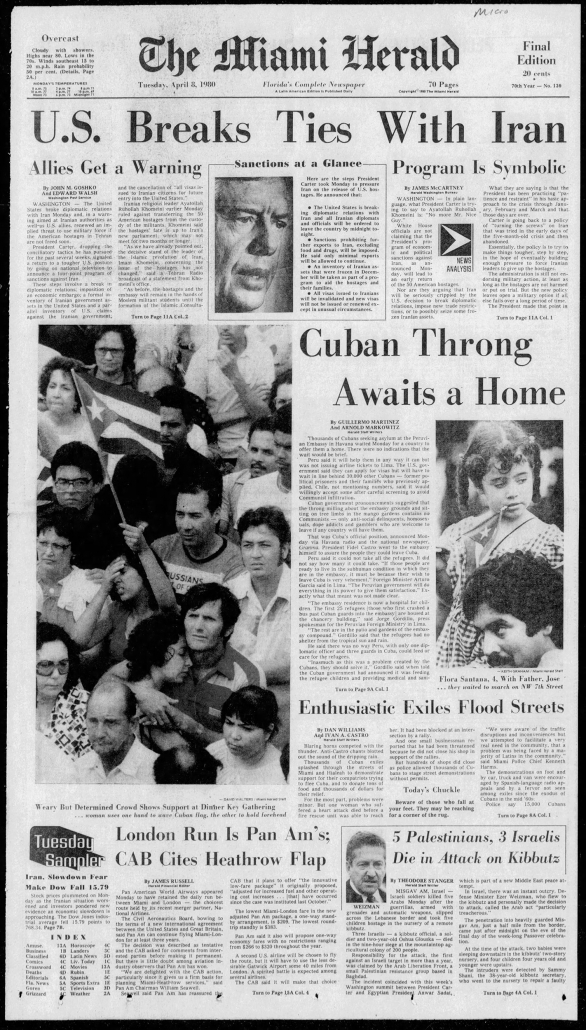

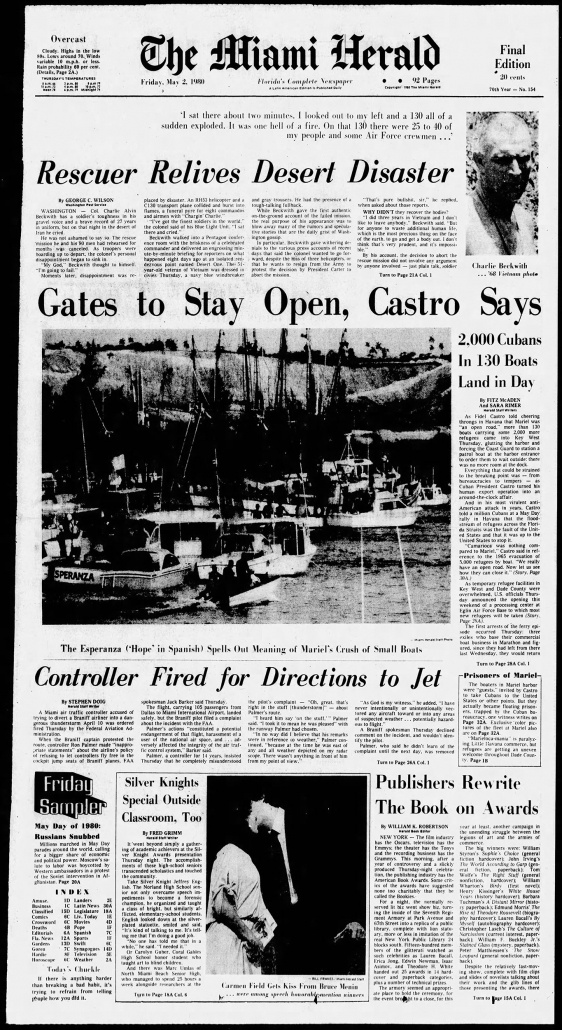

Throughout the exhibition the visitor is presented with over 75 front covers of the Miami Herald spanning from 1903 to 2020, whose headlines prove that journalism really is the first draft of history. Headlines, as we know them today, did not come into use until the late 19th century when increased competition between newspapers led to the use of bold-faced, attention-grabbing streamers across the front page. Traditionally, a paper’s headline is reflective of what a society has deemed important and “newsworthy.” There is much to be learned about a community through the exploration of what it chooses to write about as well as what it chooses not to write about. Headlines! offers a vital retrospective of the shifting values found within the ideologies of both Miami and the rest of the nation for the past 117 years.

The Miami Herald, one of the most successful newspapers in the United States, has been awarded 22 Pulitzer Prizes and has retained a faithful readership for over 115 years. The paper has been a champion of journalism and the arts – it stands as breeding ground for hard-hitting editorials, compelling photojournalism, and thought-provoking illustrations. It’s a resilient institution, overcoming and thriving through the advent of competing mediums such as radio in the 1930’s and television in the 1950’s. Presented at the turn of the decade and at the dawn of a new digital era, Headlines! prompts visitors to re-examine the contemporary editorial landscape and observe the impending metamorphosis facing print-media today.

Curated by Malcolm Lauredo & John Allen

Produced in association with the Miami Herald

Presented by the Knight Foundation

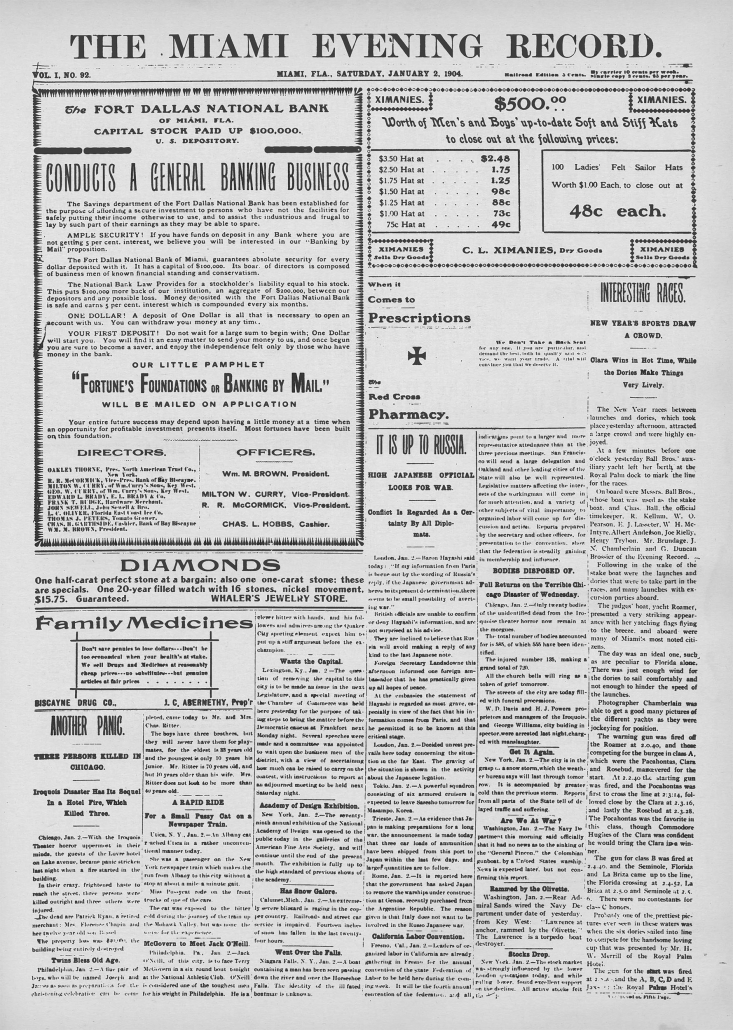

1903 – 1910

A Prequel to the Miami Herald; The Miami Evening Record

The Miami Evening Record quickly became a vehicle for bold community advocacy. Within a year of its founding, Stoneman had successfully editorialized for the creation of a charity hospital which would serve Miamians regardless of how much money they made. He was also the only local newspaper editor to skeptically look at the 1909 plan to drain the Everglades.

The most defining feature of the Evening Records’ first few years was perhaps its fearless opposition to Henry Flagler, the Gilded Age railroad mogul who was largely responsible for the city’s founding less than ten years earlier. While Miami’s success and existence were largely owed to Flagler and his investments, there was a growing discontent among the community because of the monopolies he held in the city’s businesses and political life. Unlike other local newspapers at the time, the Evening Record railed against the nepotism, negligence, and corruption found within Flagler’s companies and political representatives. This was done at great personal risk to the newspaper’s prosperity, given that a large portion of the marketing income came from Flagler’s advertisements.

As Miami’s population grew, so too did the readership of the Miami Evening Record. In just a few years’ time, Stoneman and his partners were doing so well that they bought a two-story building at the southwest corner of what is now South Miami Avenue and Second Street. In 1907, they bought out a failing paper and merged it with the Evening Record. It was also in 1907 when the newspaper renamed itself the Miami Morning Record began publishing in the morning rather than in the evening. The paper was booming and so was the city.

However, it was in this slew of growth when the paper had incurred a heavy indebtedness to the East Coast Company, which was owned by Henry Flager. Its editorial potency began to wane and Miami’s economy turned towards a downward path, culminating in the Panic of 1909 which caused banks to fail and business to close. By the summer of 1910 the newspaper was in serious trouble. Not only had circulation declined, many of the advertisers were unable to pay their bills. With the newspaper paralyzed at the precipice of bankruptcy, a herald of things to come took the shape of a neatly presented man with thick-rimmed glasses named Frank B. Shutts.

Frank Stoneman c. 1932

Paper boys delivering the Miami Evening Record in downtown Miami c. 1906

1910 – 1920

The Birth of the Miami Herald

Because of the reputation Shutts had gained as the receiver for Flagler’s bank, and perhaps because he represented their most important creditor, Stoneman and The Miami Morning News hired him to put the paper back on its feet. A deal was quickly brokered which resulted in Flagler purchasing the paper and paying off its debtors in exchange for lenient coverage of his business operations. This sort of fraternalization between the financing and editorial departments would later be TKVERB by the Knight brothers. Shutts was appointed publisher, and Stoneman was appointed editor and on December 1, 1910, the newspaper’s name was changed to The Miami Herald. Shutts, a man who never had any intentions of running a newspaper, fell in love with the newsroom and purchased the Miami Herald from Flagler two years later following a petty disagreement over the employment of a chauffeur. Henry Flagler passed away the following year, marking the end of an era.

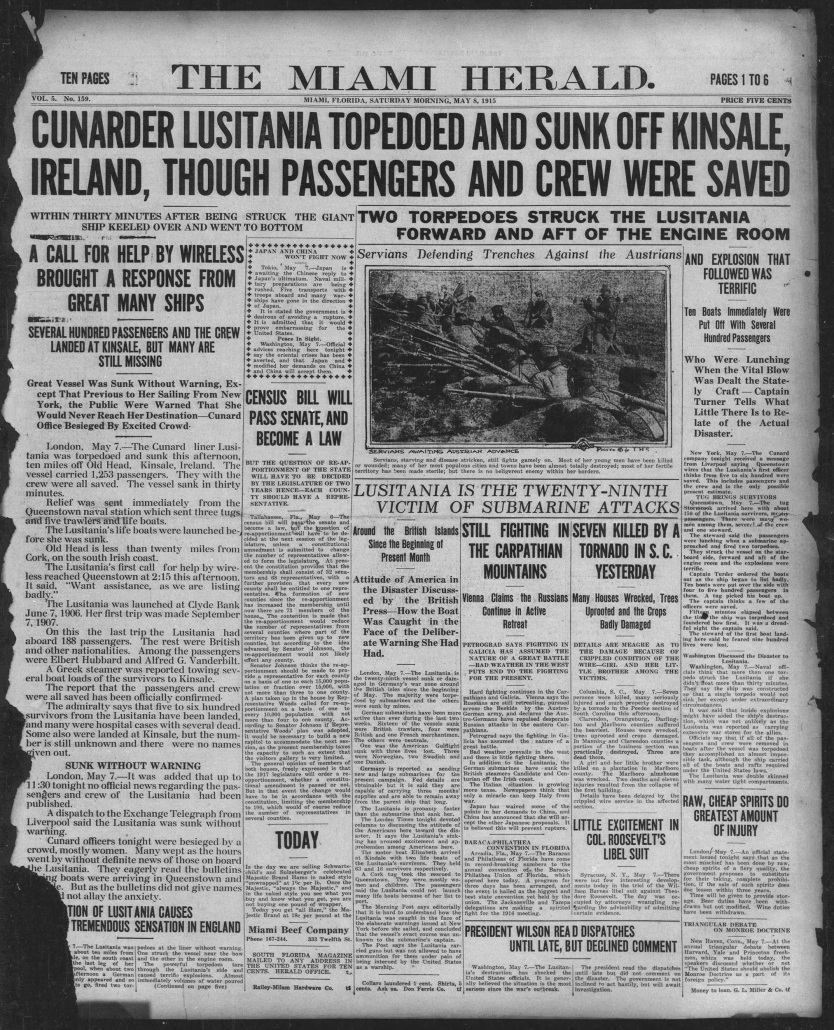

The Herald, under new management, navigated its rebirth and experienced a new era of evolution. Its first major improvement came in 1911 when it became Miami’s first newspaper to receive the Associated Press’ worldwide news distributionCK*. As its circulation started to make a noticeable gain, so did its advertising. However, it was the Herald’s breaking coverage of the sinking of the Titanic in 1912 that sparked new highs in its readership. The paper successfully editorialized for the creation of Tamiami Trail, the first road which connected Florida’s southern east and west coasts. In 1915, the Miami Herald hired its first woman reporter, Marjory Stoneman Douglas, starting to write for its society column but would soon go on to report from the streets of Paris during the first World War.

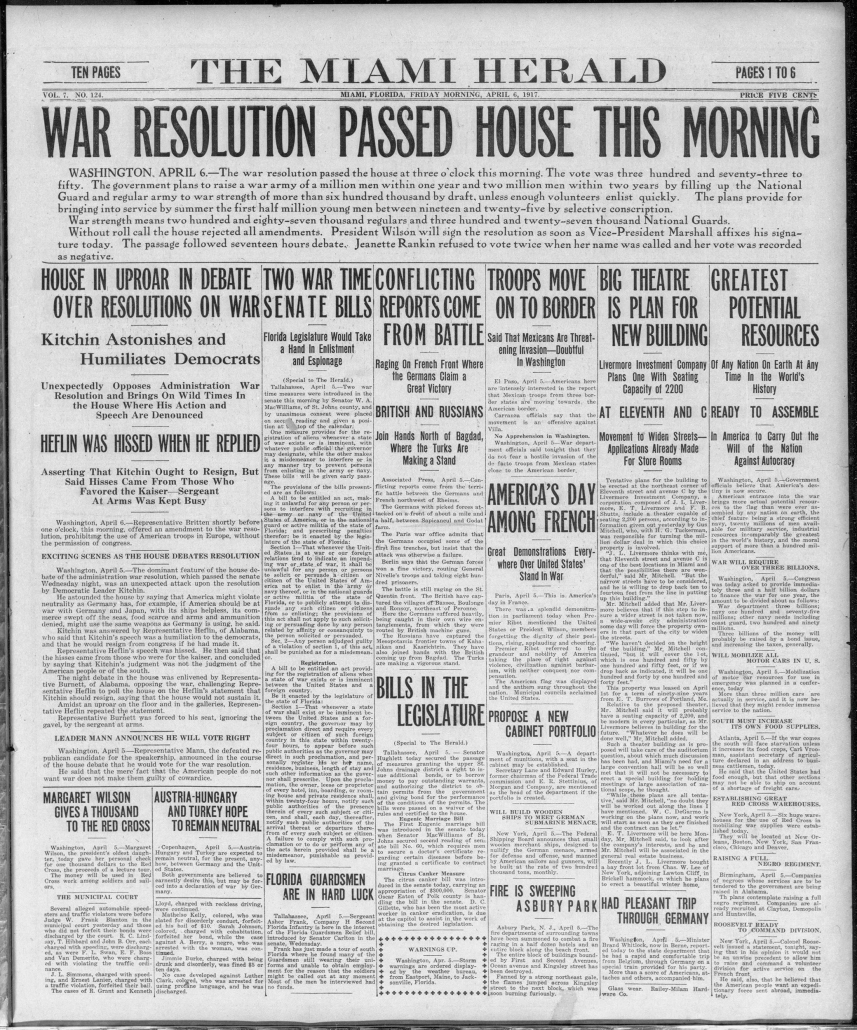

When war broke out in Europe in 1914, the Herald was still a small-town paper in a small southern town. Miami and its writers were not immune to the influence of the moralist movement sweeping the nation, which advocated temperance, bible thumping and conservative moral values. The Herald was not insusceptible to the contemporaneous social climate, best exemplified by its printing of Sunday’s sermon on Monday and its habitual coverage of “come to Jesus” fundamentalists such as Billy Sunday. By 1916, however, the nation was growing prosperous from its trade with belligerents, and so was Miami, which in 1916 experienced a building boom. The newspaper began to move away from its fundamental values and even opposed the passing of prohibition in 1919.

In 1910, Miami’s population was 5,500. But by 1920, its population had rocketed to 30,000. However, this growth spurt was only a hint of the exponential evolution and innovation to come to both the city and Herald during the Roaring Twenties.

Frank Shutts, c. 1910’s

1920 – 1937

The Boom, the Bust, the Depression, and Redemption

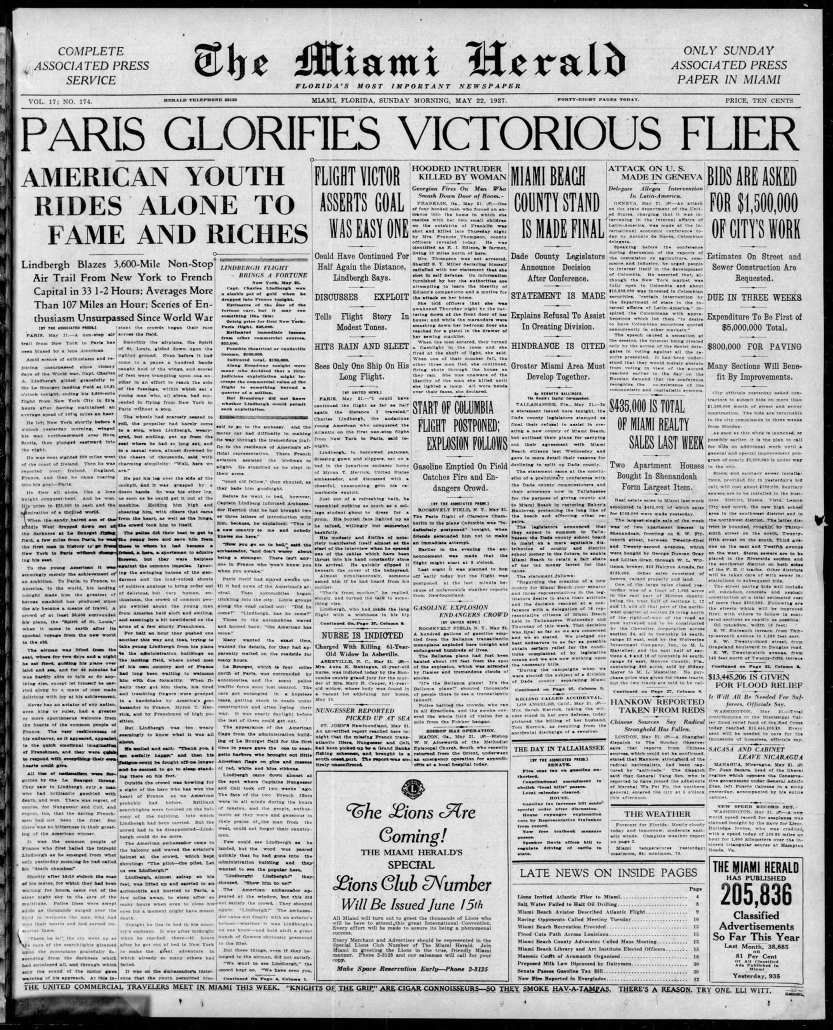

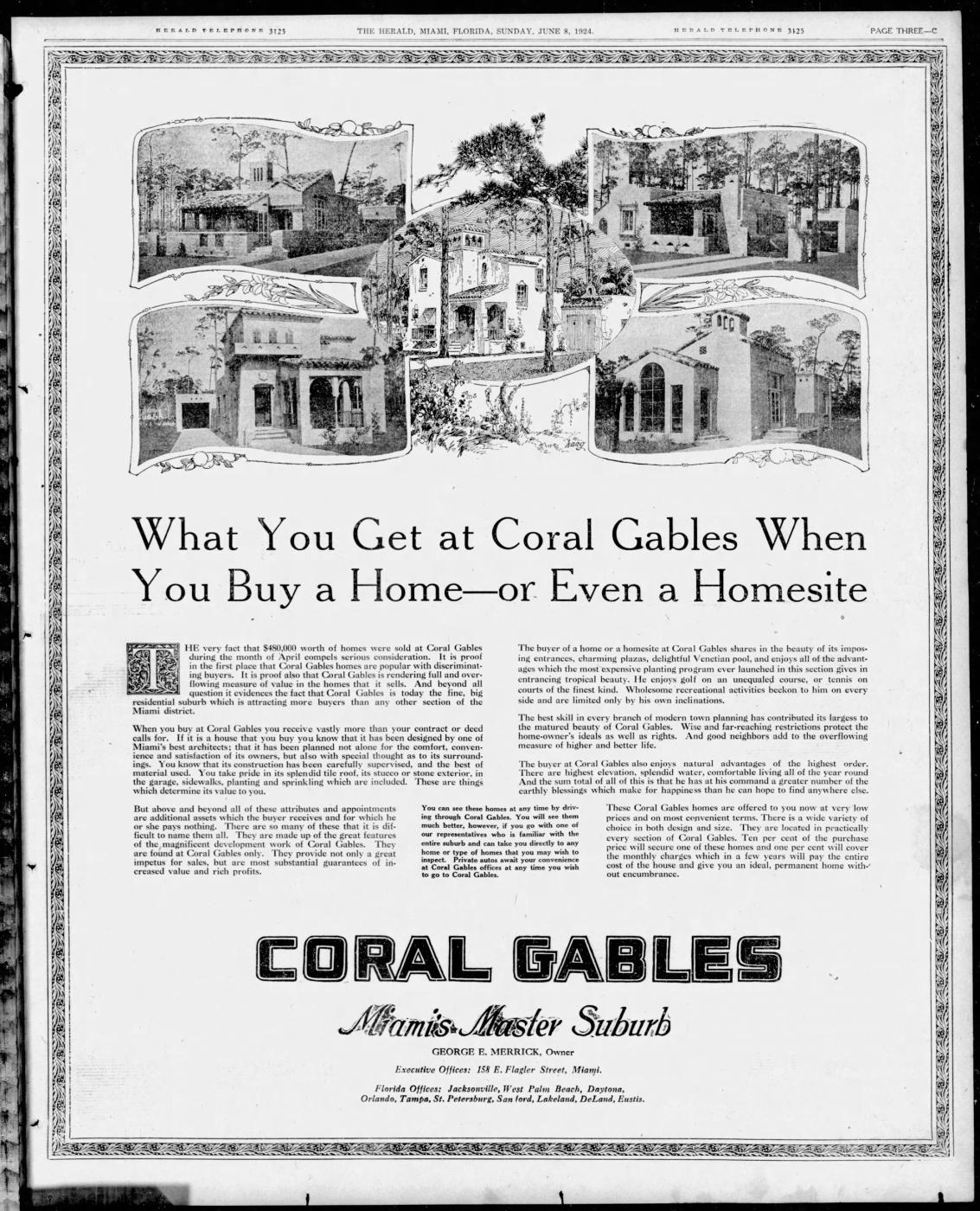

Miami’s boom was largely funded by real estate and development. So too was the Herald’s growth in the 1920s: For every home or building that was built, a barrage of beautiful, full-page advertisements would find its place in-between the pages of the Miami Herald. The era bred a culture that revolved around property, development and speculation. Americans from across the country flocked to South Florida to bask in the sun and get rich quick selling real estate. In the summer of 1925, new editors and reporters came to the Herald almost daily, sometimes only working a week, seldom longer than a month. Most resigned to become real-estate salesmen.

Regardless of its quick employee turnover rate, for thirteen months in 1925 and 1926, the Miami Herald was the largest newspaper in volume of business in the world, toppling the great papers of London, New York, Chicago and Los Angeles. It set a world record in 1925 with 42.5 million lines of advertising, 12 million more lines than any newspaper had ever carried in a year’s time. The Herald realized it needed to update facilities to keep up with the boom-time demand. In 1925, construction began on a new four-story building behind its Miami Avenue headquarters. Refusal to advertise the KKK as another social club.

As a boom-time newspaper in a boom-time city, the Miami Herald became the city’s advocate throughout the 1920s. It did everything it could to stoke the flames of Miami’s growth, running editorials encouraging development, reporting on the city’s successes, and rarely strayed from its positive messaging. The paper sang the city’s praises but was cautious to report on topics might stifle investment and development. However, the newspaper’s compulsion to report on the good and downplay the bad came to a head as the decade did.

While the first half of the 1920s marked one of the Herald’s golden ages, the latter half marked some of its most trying times. Signs abounded that this boom was approaching its bust, though one would never have known from reading the Miami Herald. As much as Miami benefitted from the Great Florida Land Boom, its infrastructure began to prove inadequate to support this massive period of growth. The Florida East Coast (Miami’s lifeline to rest of the country put an embargo on the city after large volumes of imported lumber led to train-station employees being unable to unload as fast as they were receiving, which backed up the entire line. To make matters worse, a ship capsized in the harbor, rendering the port inaccessible for almost six weeks.

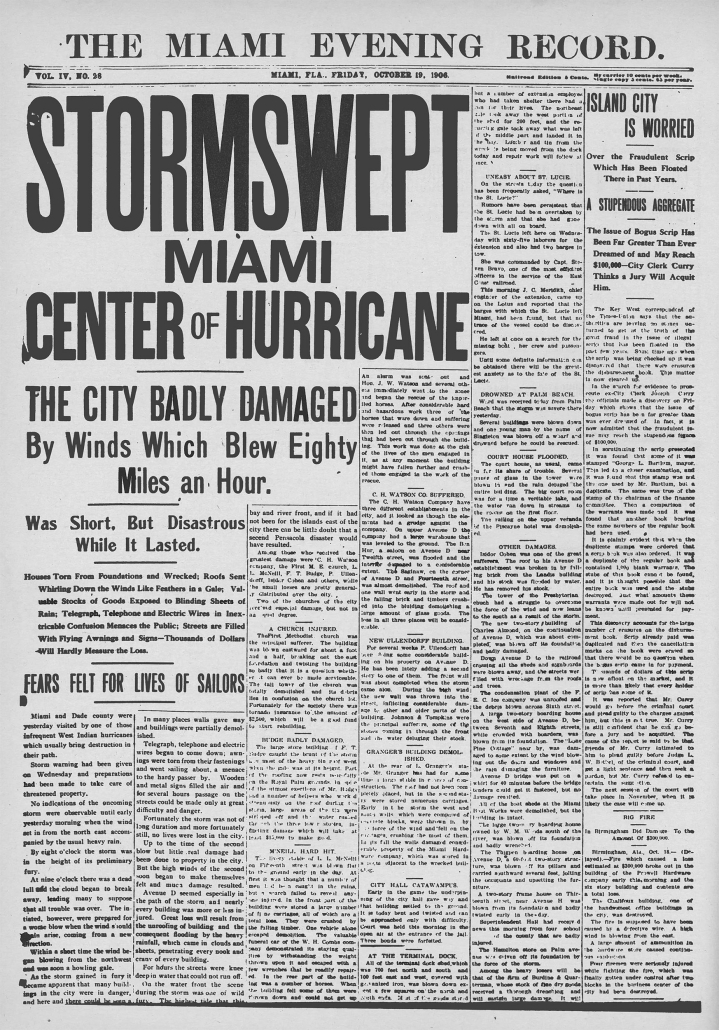

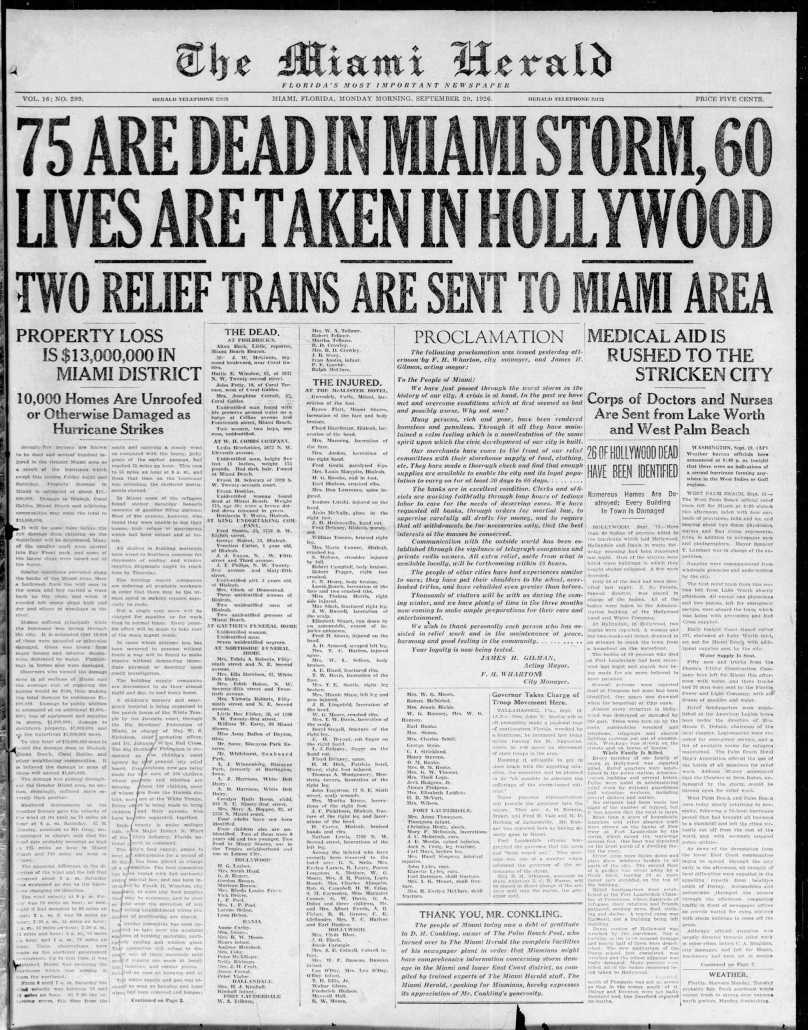

This hurricane, later called the Great Miami hurricane, acted as a catalyst, popping what was left of the real-estate bubble and violently shoved Miami into the doldrums of the Great Depression three years before the rest of the nation. After the 1926 storm, the fortunes built on speculation would vanish and Miami would lose nearly half of its boom-time population. Readership for the Herald would also decline, its volume in advertising becoming a dim shadow compared to the boom years.

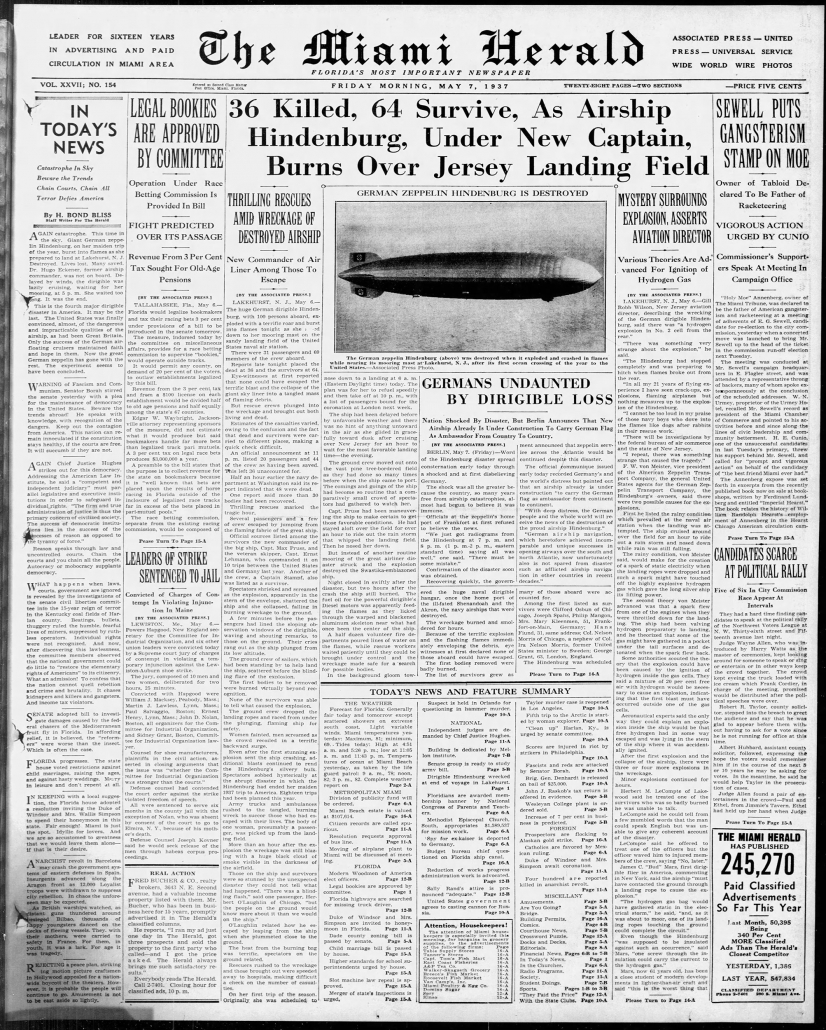

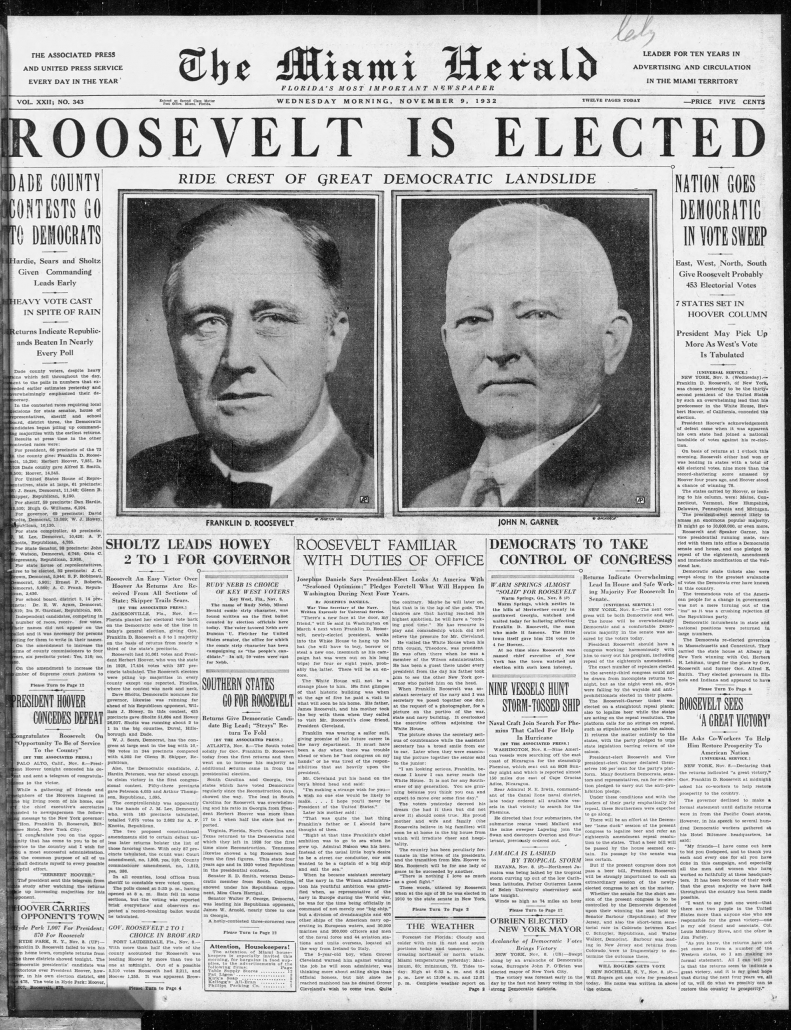

As the Great Depression swept the nation, South Florida saw a small pick-up in its population due to disenfranchised workersCK* migrating from the north. There was a saying that if you were going to starve, you might as well do so in comfortable weather and in a beautiful environ. The end of this era of unchecked growth gave birth to a new one: the Age of Radio.

The radio began to pick up in popularity in the late 1920s and throughout the Great Depression, culminating in over 60 percent of Americans owning a radio by 1934. It marked a time when newspapers were not only having to compete against other newspapers, but against different mediums.

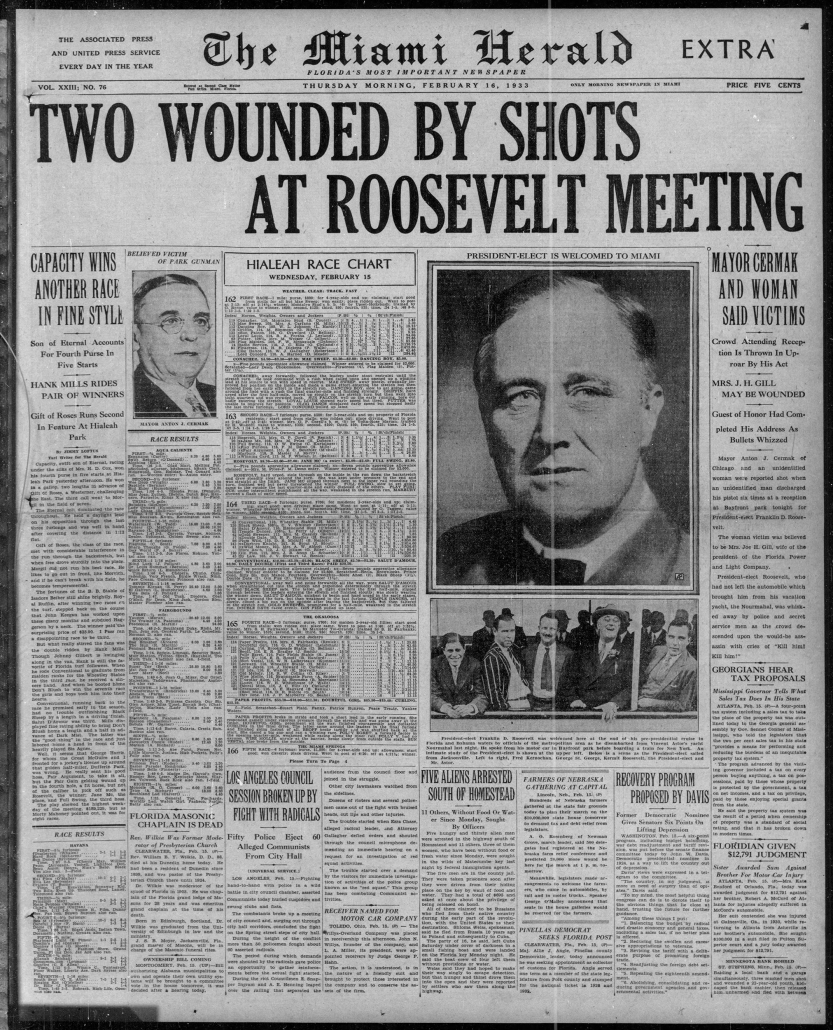

A resilient institution, the Miami Herald stabilized its circulation in the 30s and, once again, began to experience steady growth in readersCK*. It reoriented itself, doing away with the sensationalist, “everything’s great” headlines which characterized the 20s, and adopted a more dependable and serious front page. The paper turned its eyes to towards the overcrowding and obscene living conditions in Overtown (then called “Colored Town”) and editorialized the expansion of resources made available to Miami’s black community. These efforts eventually culminated in the creation of Liberty Square, the first public housing project in the southeastern United States.

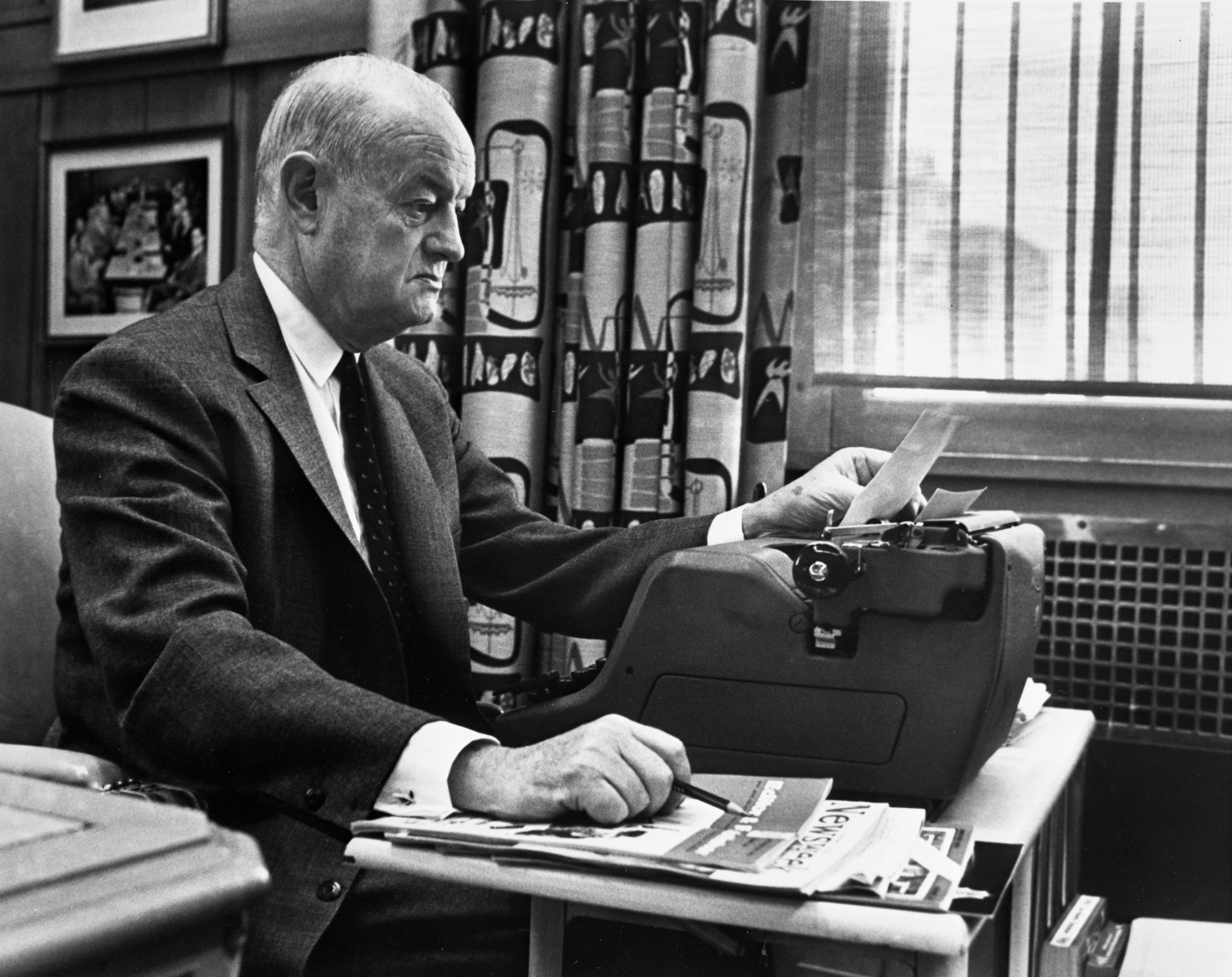

Shutts, nearing his mid 60s, began to show less and less interest in the news and editorial content published in the Miami Herald. Stoneman also began to demonstrate a certain amount of waning himself, not delivering the same potency as perhaps a few years before. The Herald, a ship without an impassioned captain behind its helm, could have almost been considered adrift before John and James Knight joined the voyage.

Full page advertisement found in the Miami Herald in the mid-20’s. Such advertisements, both commonplace and lucrative and fueled, the Herald’s growth in the 1920’s.

Miami’s September 17th & 18th 1926 hurricane. The storm a was the final blow to South Florida’s economy prior to the nationwide depression three years later.

1937 – 1958

Knights of the Fourth Estate

After the Knight takeover, the newspaper began to diligently cover local corruption, most noticeably in the Herald’s role in exposing a political scandal in 1937. Herald reporters helped break the story of City of Miami commissioners attempting to collect a bribe from the president of Florida Power & Light (FPL) in exchange for agreeing to a power rate that would save the utility company millions of dollars. The newspaper would again report on City of Miami corruption in 1939. It was over, of all things, milk: A herald reporter led an editorial campaign over the sale of unpasteurized milk in Miami, which was becoming a serious health crisis resulting in over 1,000 cases of undulant fever a year. No other campaign in the paper had had ever been given so much space. Miami mayor E. G. Sewell, who very much preferred his milk unpasteurized, was so offended by the pasteurization movement that he declared, “Who is John Knight to insist upon an ordinance of milk?” The Herald’s efforts were largely successful and nearly everyone in Dade County stopped buying unpasteurized milk. The undulant epidemic came to an end. It was one of the first times the Herald had sunk its teeth into a story and refused to let go.

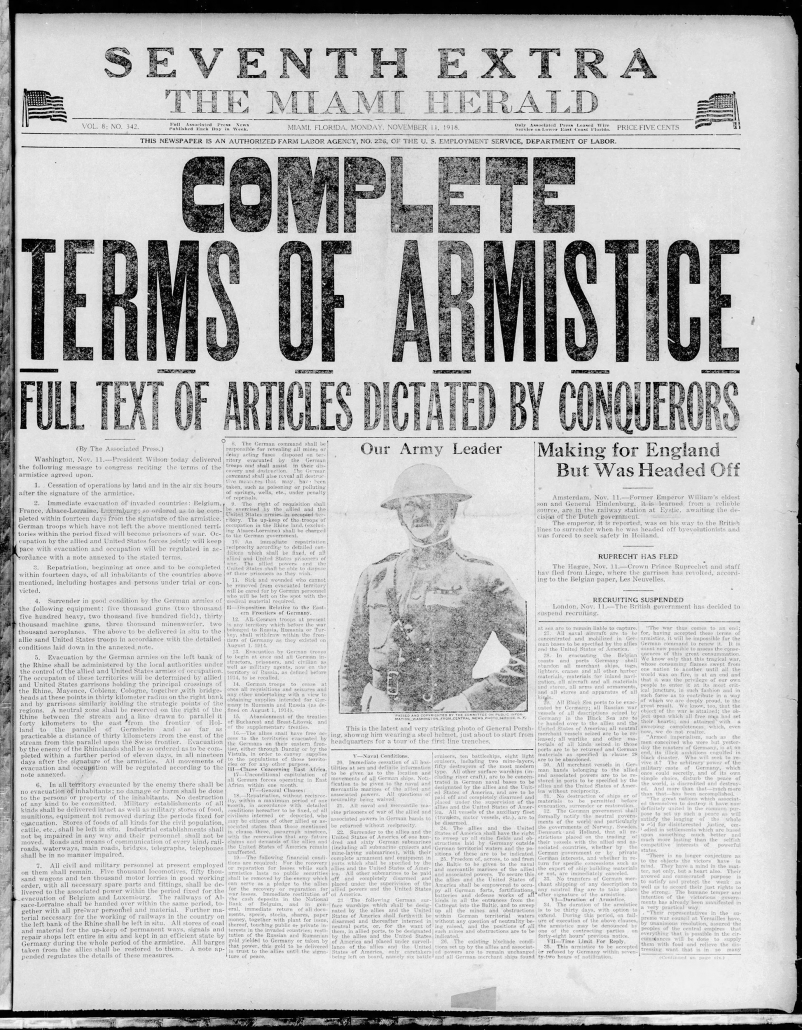

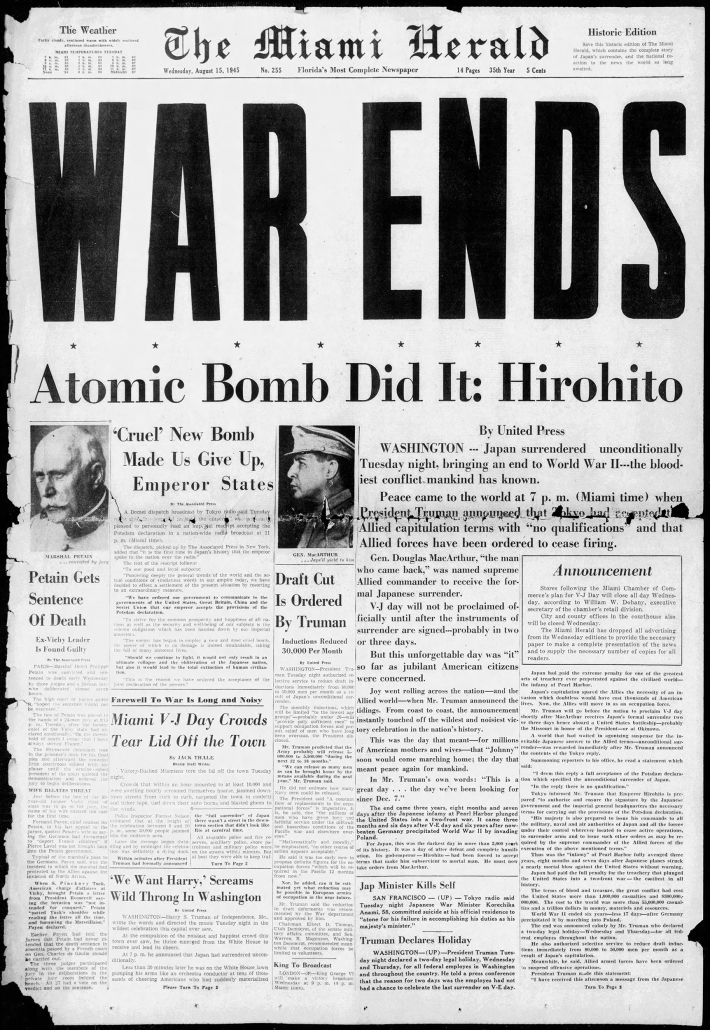

Four years after the Knight takeover, the United States entered World War II. The war did much to reorient Miami and the Herald. Miami, whose tourism economy faltered at the onset of war in Europe, found itself alive again: streets were flooded with thousands of soldiers whom had come from all over the country to train before fighting abroad. Hundreds of vacant hotels were transformed into military training facilities and soldiers were conducting marching drills up and down Biscayne Boulevard. The Herald changed too. Not only had the paper regained the circulation it lost during the early part of the war, it had become a vital source of information regarding price controls, rationing, dim-outs and other wartime activities. It had become a public-service newspaper, acting with a newfound sense of civic duty. Due to wartime rationing and shortages, the Herald was often forced to run a small, seven-page paper that left little space for advertisements, news and editorials. The Herald would, sometimes for weeks, publish a paper with no paid advertisements to leave space to cover important news stories to those in Miami with family in the war.

Then on September 15, 1945, soon after the war ended, a hurricane hit Homestead. During the storm, the Richmond Airfield base caught fire and its enormous airplane hangars burned down—signaling the end of Miami’s wartime era. When the editors, who were holed up at the Herald during the storm, heard about the fire they sent a reporter and photographer to cover the scene. A car was filled with thousands of pounds of Linotype to make sure they wouldn’t blow away. The Herald’s coverage of this hurricane was its first attempt at doing all-out reporting on an incoming storm and the damage it left behind. This was in sharp contrast to pre-Knight policies that discouraged storm coverage because it caused “undue alarm” and portrayed the city in a bad light. (The Herald would continue to produce a culture of storm reporting ultimately leading to its 1992 Pulitzer Prize for its humanitarian effort after Hurricane Andrew.)

The Herald, at John Knight’s prerogative, set out to expose the deep-seated corruption found within Miami and its elected officials who had essentially turned Dade and Broward counties over to be run by the Mafia and old Capone gang after WWII. These gangs, most notably the S & G Syndicate, would take over all of the newsstands near the swanky hotels and would illegally operate them as gambling facilities. One could walk up to newsstand on Miami Beach, slam five dollars on the table, buy a Miami Herald and place a bet on a race at Hialeah Race Track. These small newsstands and the illegal gambling operations within them would generate enormous sums of untaxed income, much of which would trickle into the pockets of local officials who would turn a blind eye to the nefarious operations. In 1950, the Herald won a Pulitzer Prize for its watershed campaign against Mafia-related corruption in Miami’s government. Their efforts resulted in the conviction of Dade County’s Sherriff, who had come into office with assets amounting to 7,000 and was proved to have accumulated 77,000 in just four years of office. This conviction came amidst an entire tribunal of cases aimed at rooting out corruption that was spurred on by the Herald’s call to action.

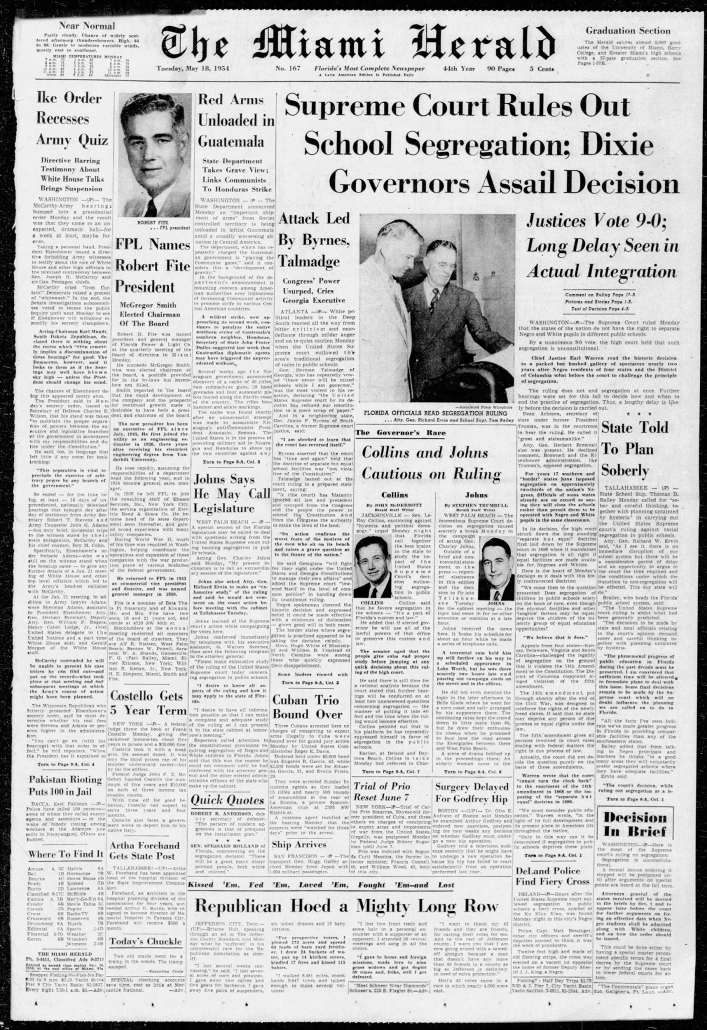

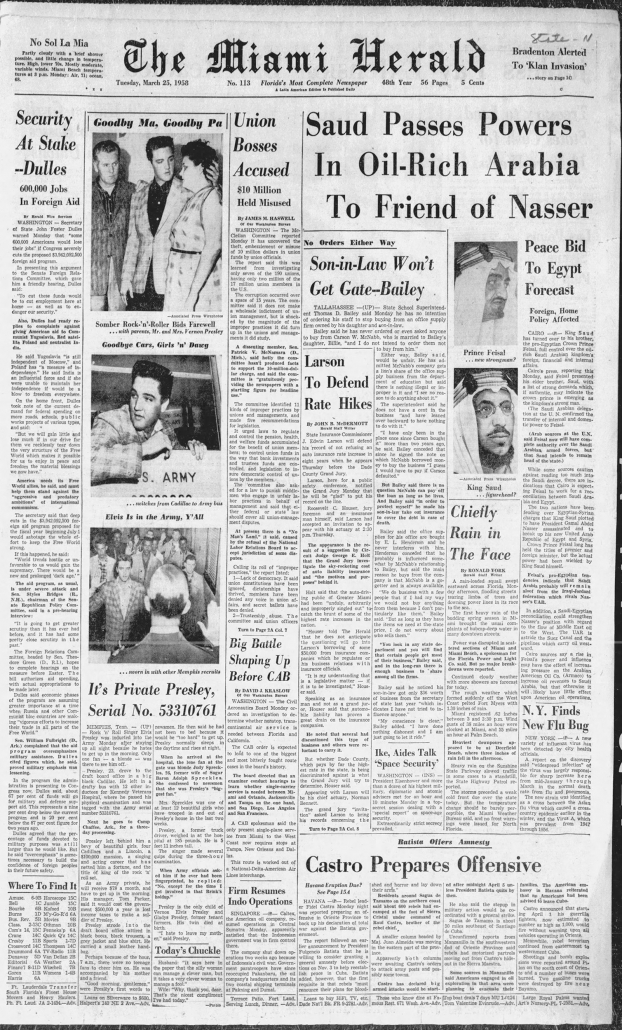

Throughout the desegregation era of the 1950s, John Knight was reportedly critical of how casually Herald journalists were reporting on the topic. Because of ignorance and fear, the mainstream press, almost exclusively run by white men, didn’t recognize it was in the midst of one of the most important moments in American history. It was an era where stories about Korea, Elvis and Russia sold newspapers—not civil rights. This is not to say that civil rights movement wasn’t written about—they absolutely were—those stories were just rarely found plastered across the front page.

By the early 1950s, a nation-wide revolution in newspaper writing had planted its seeds in Miami. This new writing philosophy preached the doctrine of primitive simplicity: “short words, short sentences, short paragraphs, shorter stories.” Newspaper writers were encouraged to “talk straight.” The lush, expressive and meandering newspaper writings from the first half of the century was giving way to a new, more streamlined delivery of writing.

Meanwhile, there were no signs of a slowdown in Miami’s population boom or in the Herald’s circulation growth. It needed to expand its facilities to keep up with the rising demand. In 1953, the Knight brothers tried to buy a building adjacent the Herald’s headquarters downtown only to find that an exiled Cuban politician had already purchased the building. This moment, one that seemingly foreshadows the Cuban influx just around the corner, turned the Herald’s eyes to the shores of glistening Biscayne Bay for its new place to call home. Many others would soon need a new home to call their own as well. While the Herald scattered to consolidate enough land for its new headquarters, a political conflict was looming only 90 miles across the bay that would go on to transform Miami into the Casablanca of the Caribbean.

1959 – 1989

Wealth, Turmoil, Technology and Diversity

While the 1960s can be characterized as a period of increased riches and development, it can also be remembered as an era of racial violence, cultural traumas and hard-fought activism. The Miami Herald embodied the changes sweeping the city. As its staff continued to grow throughout the 1960s, so did its diversity. More and more opportunities for advancement were being extended to more employees (not just the white men) and the newspaper was on its way to becoming a more inclusive and representational publication.

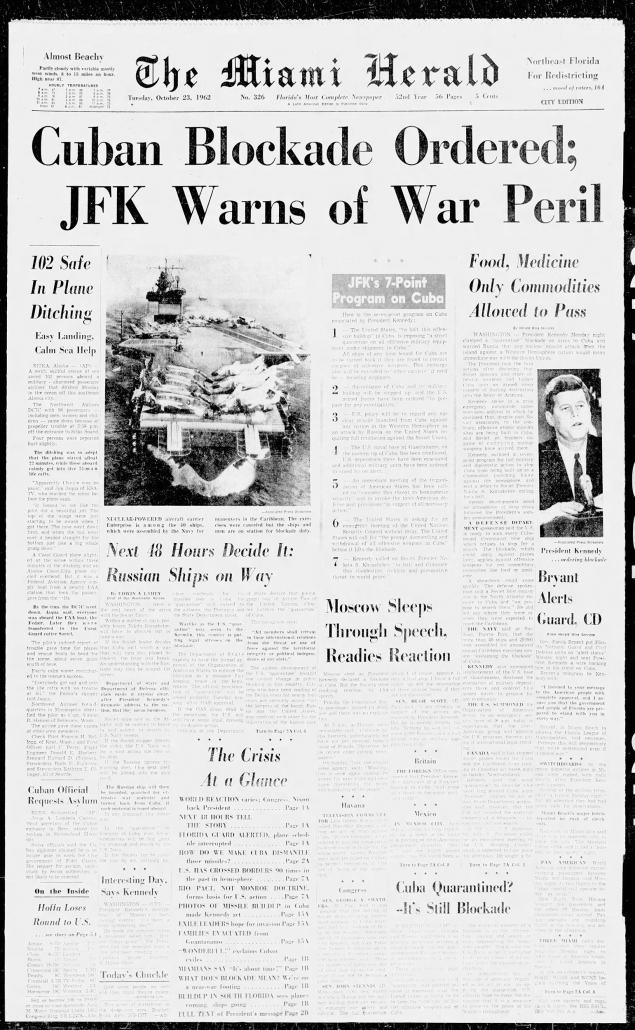

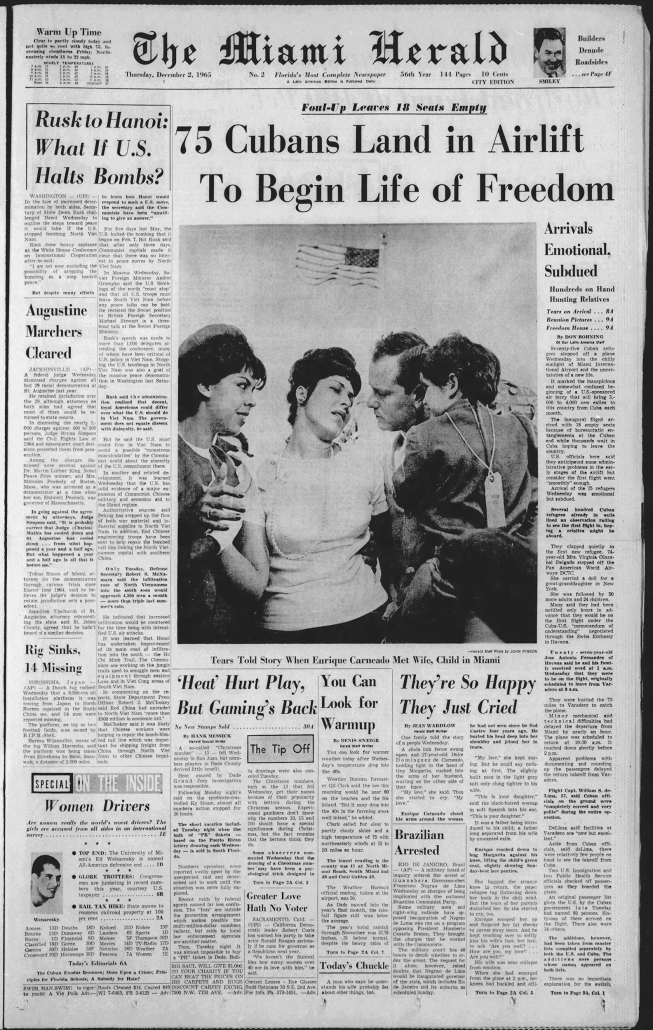

After Fidel Castro was released from prison in Cuba in 53, he came to Miami to raise funds for an invasion army that he would train in Mexico. He came to the Herald and ask that they run a story. Nobody took the man seriously, as political unrest had become common place on the island-nation and a throw-away blurb was published deep within the folds of the newspaper. The series of events following Castro’s grab at power would take priority in headlines across the nation for years to come. The Cuban story would perhaps be the largest local story ever covered by the Miami Herald. It was an odyssey that would involve the arrival of Cuban refugees in Miami, the breaking of diplomatic relations between the U.S. and Cuba, the Bay of Pigs invasion and the Cuban Missile Crisis.

After the Cuban revolution, 100,000 refugees immigrated to Miami believing they would return to Cuba after Fidel was thrown out of power. When it became clear that nobody was going back to Cuba anytime soon, many Cubans starting settling in and finding entry-level jobs at places like the Miami Herald. Roberto Suarez, an exiled Cuban lawyer, found work inserting flyers into the paper and would eventually rise to become the president of the Miami Herald and later publisher of el Nuevo Herald.

Set against the backdrop of desegregation, the 1960s were part of a continued era of racial strife and activism in Miami. While Miami was a hotbed of sit-ins and protests, these issues were rarely covered on a day-to-day basis and were almost never featured on the front page. Issues facing black residents in Miami were largely unrepresented in mainstream newspapers. This led to the widespread popularity of other local newspapers such as the Miami Times, which was black-owned and employed black journalists who understood their community’s unique experience in Miami. The Herald had often led campaigns aimed at racial and social justice, first exemplified in the 1930s when they campaigned for the creation of Liberty Square. Continuing this legacy, investigative reporter Gene Harris won the Herald its second Pulitzer Prize in 1967 for reporting that helped save two innocent black men from execution. As the 1960s came and went, the City of Miami emerged reborn. It was transformed from a small southern city into the beginnings of an international city – one whose glimmering bay would serve as a beacon of freedom to those in South America and the Caribbean in the decades to come.

By the 1970s, the Miami Herald had grown so much that it surpassed the New York Times in space given to news coverage. Alvah Chapman, who had a very different managing style from the Knight brothers, had introduced the Herald to the computer age. He worked to modernize, streamline and improve production. The Sunday edition would often run over 400 pages and occasionally reached 500 pages. The rising cost of newsprint and ink in the middle of the decade, however, prevented newspapers from getting bigger and bigger. While the computer’s presence in the newsroom didn’t put writers out of the job, the production department was completely restructured. Many production workers, whose trades had been routine in newspaper making for almost a century, lost their jobs to automation and were forced to look for work elsewhere.

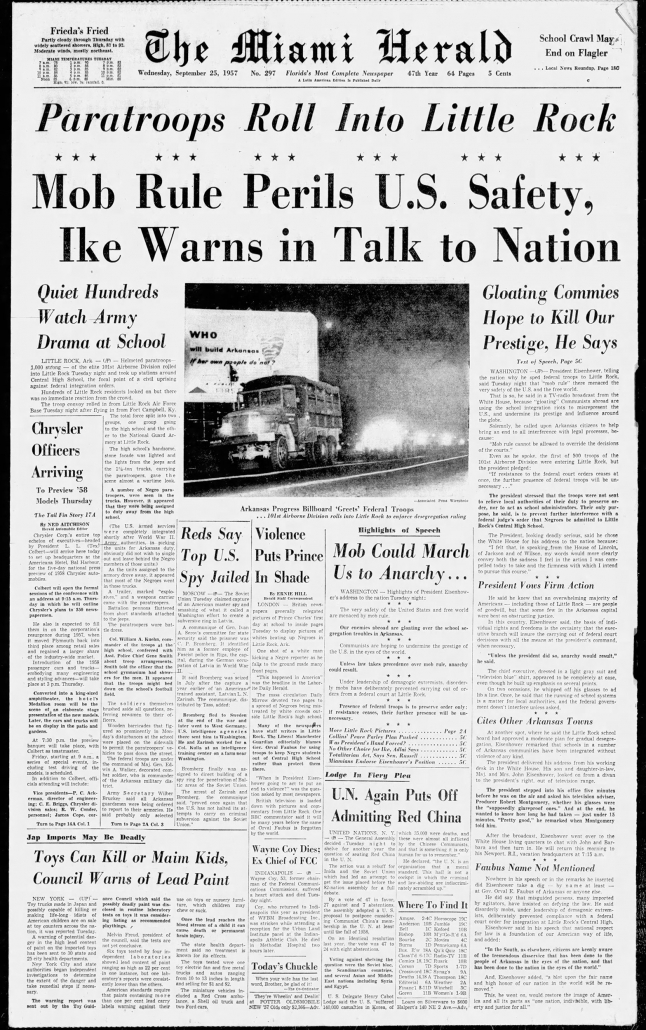

Meanwhile, many of the reformations born of the civil rights movement had not been thoroughly implemented in Miami. After a push from Dade County commissioners? in the 1970s, Miami finally started tackling the desegregation of public schools. Once integration began, it led to some of the ugliest moments of the civil rights movement, including riots at Miami Palmetto Senior High and Miami Edison High School. Unfulfilled promises, residential displacement and habitual harassment by the police garnered a sense of resentment from many of Miami’s black residents, who felt the city had left them behind.

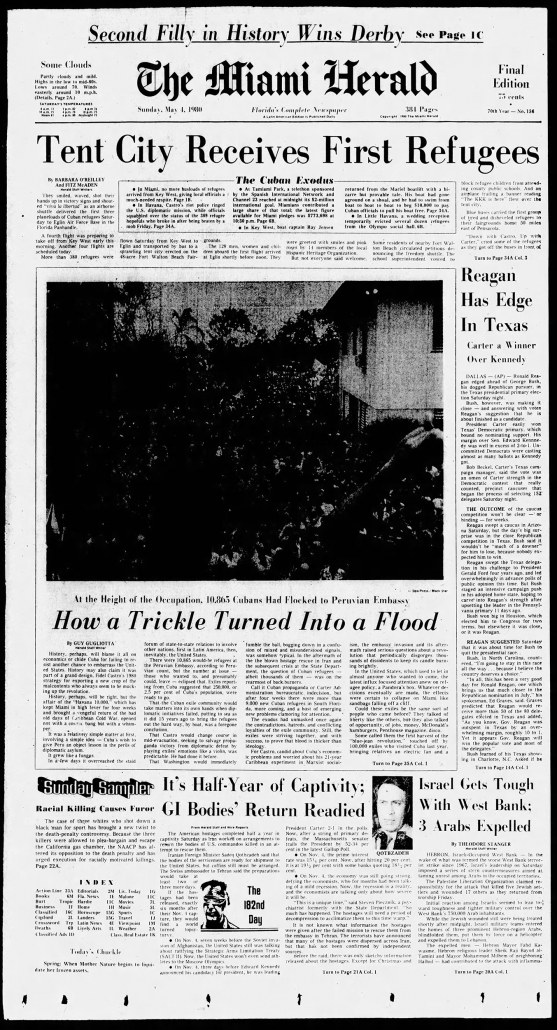

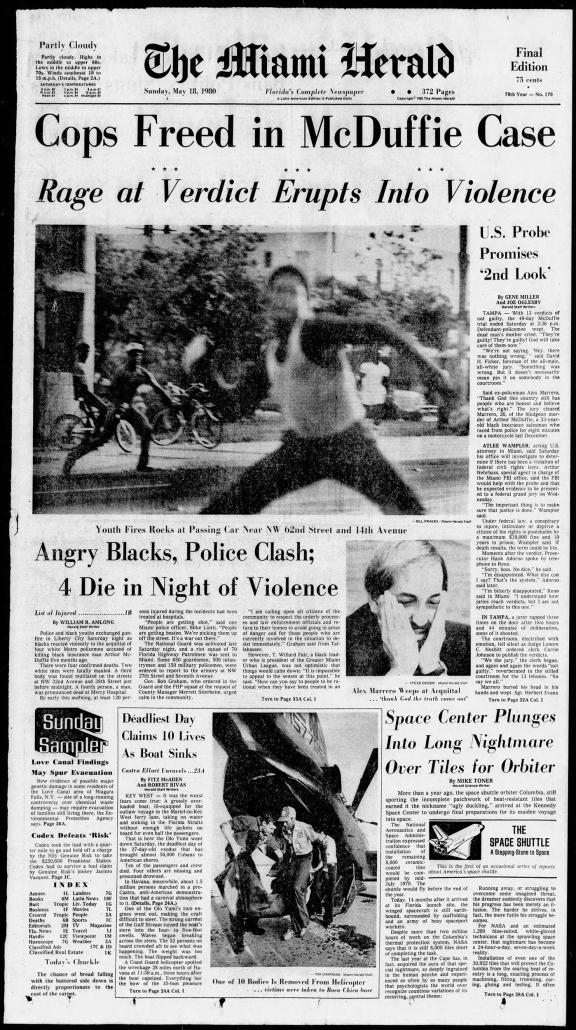

The 1980s were rung in with an explosion of anger. When four Miami police officers were acquitted for the brutal murder of black salesman Author McDuffie, riots broke out in Liberty City, Overtown, Brownsville and Coconut Grove. The acquittal acted as a catalyst; fires consumed entire city blocks as people took to the streets to mourn. An estimated 3,500 National Guard troops stormed the city and, after three days of conflict, 15 were left dead, 350 were injured and 600 were arrested. The McDuffie riots were the deadliest since the 1960s (it held that title until the 1992 Los Angeles Riots). Just one month earlier, at the onset of an economic downturn, Fidel opened Cuba’s borders triggering a second massive exodus of Cubans into Miami. Haitians and Cubans would arrive in boats and granted refugee status. This continued for six months, resulting in tent cities being erected under bridges and approximately 150,000 refugees being processed in Miami.

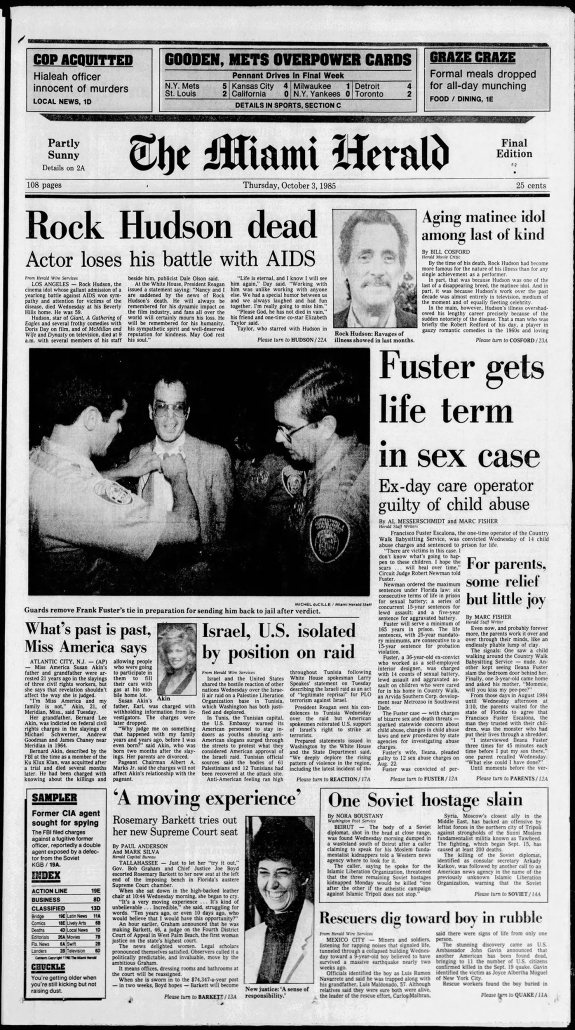

It can be said that journalism thrives in the worst of times because where else can journalism be of better use? In the 1980s, the Miami Herald was operating at a time in which Miami had become “Paradise Lost.” It was a time when racial tensions were at their highest and when cocaine and violence would spur economic growth. It was a time when Miami had become the murder capital of the world. But against this backdrop in the 1980s, the Miami Herald won eight Pulitzer Prizes—a major accomplishment considering that the paper had only won three in the prior 76 years.

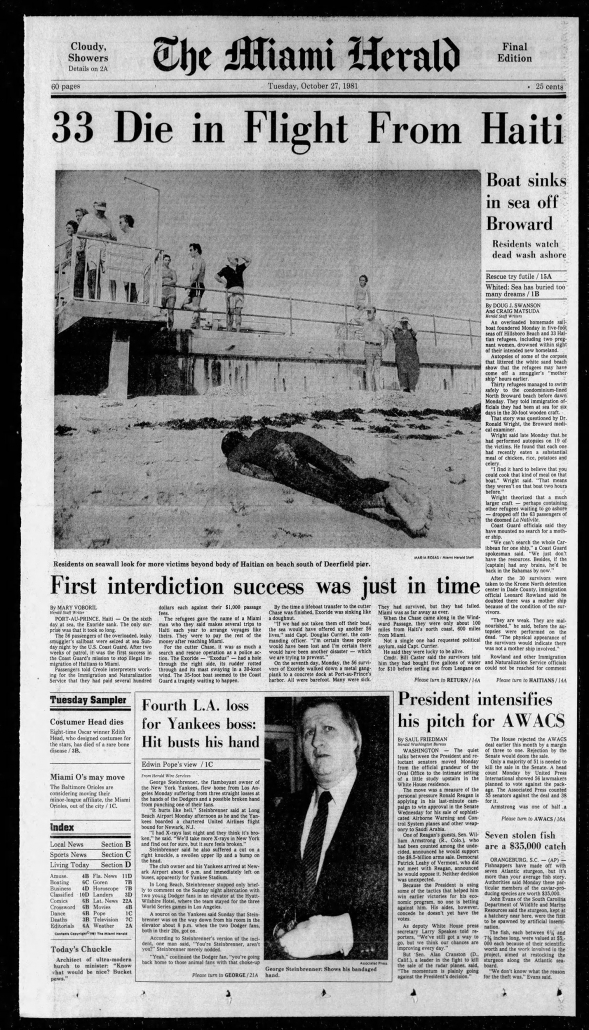

In 1980, Herald writer Madeleine Blais was awarded a Pulitzer Prize for feature writing for her stories chronicling an aging WWI veteran’s attempts at having a dishonorable discharge expunged from his record. Blais was the first woman to win a Pulitzer at the Miami Herald. One year later, another woman, Shirley Christian, won a Pulitzer in international reporting for her dispatches in South America. More Herald staffers were awarded Pulitzer prizes for railing against illegal Haitian detention camps and for photographs portraying the decay and subsequent rehabilitation of housing projects during the crack-cocaine epidemic. The newspaper was recognized for its national reporting as well, receiving another Pulitzer for its persistent coverage of the Iran-Contra connection. In 1989 Dave Barry was awarded a Pulitzer for using humor to provide unique insights into serious problems.

The Miami Herald met the 90s with a dream team of photographers and writers. Newspapers were making big money and the Herald would continue bringing home prestigious awards. While the period between 1960s and 1980s gave birth to the computer, the 1990s continued to implement technological advancements which, to this day, continue to shape how people learn about and interact with the world around them: the internet.

1990 – 2020

It was a decade that witnessed dramatic change in almost every area. Technically, it started with the successful 1990 launch of the Hubble Space Telescope, while the most popular achievement was the debut of the World Wide Web, and the explosion in growth of mobile phone services. The decade ended with a world anxiously watching at midnight on December 31, 1999, when, for the first time, the new year would start with the digit “2” – cheers went up when computers and associated technology kept running without a hitch. The wait had its own name – Y2K.

In Washington, the decade began with President George H.W. Bush, followed by Bill Clinton, who was re-elected in 1996. Clinton’s second stint was rocked by scandal when he was accused of having a sexual relationship with a 22-year-old intern. Clinton denied the affair, which led to his being impeached. After a 21-day Senate trial, Clinton was acquitted. However, the “people” story of the 1990s was unquestionably the trial of former football star O.J. Simpson, charged with the slaying of his ex-wife and an acquaintance. Aired live on television in its entirety, the nine-month trial received unprecedented world-wide publicity. So obsessed with the trial it was estimated the loss in U.S. productivity had been an unfathomable $40 Billion.

These stories were covered in-depth by the Herald, as were important local stories. In 1992 the entire county staggered from the destruction of Hurricane Andrew. The first Summit of the Americas was held in Miami, acknowledging Miami’s growth on the international stage, which was also reflected in the name change from Dade County to Miami-Dade County. The decade culminated with the 1999 opening of the American Airlines Arena, and the debut of the annual music festival, Ultra.

After 10 years, during which the Herald won 5 Pulitzers, Lawrence closed this chapter of his career. He left the Herald in a strong position as the new decade dawned.

If there was a decade that marked the onset of the challenges newspapers would eventually have to face, it would be that of 2000-2010, but for the Herald there were also rewards – and a plethora of important news to cover. Alberto Ibarguen, publisher of El Nuevo Herald, became the first Latin-American publisher of the Miami Herald.

It was a decade that saw phenomenal growth in the tech markets. Important for the newspaper industry was the 2000 launch of the first mobile news, followed by Multimedia Messaging Service. These on-demand, “instant” news services would present another significant alternative to how the world received the news. Another challenge was the proliferation of “all news” channels such as CNN and Fox News. Knight-Ridder, the Herald’s parent company, jumped into the digital age.

One of the most controversial events was the Elian Gonzalez affair, which further polarized US relations with Cuba. What started as a local story quickly became a major nationwide report. A year later, one of the most significant events in recent history occurred on September 11, 2001, when terrorists hijacked four planes, flying two into New York’s World Trade Center and one into the Pentagon. The Herald used every resource at their command to relay the story as it unfolded, as a stunned nation watched it unfold live on television. On its heels came an unprecedented suspension of civilian air traffic and the Anthrax attacks launched through the US Mail. Two years later, the Space Shuttle Columbia disintegrated on reentry, killing all aboard, resulting in a 29-month suspension of the Space Shuttle Program, and the US invaded Iraq to fight an insurgency, with the deposed President Saddam Hussein being captured by US special forces.

In 2005 Ibarguen left the Herald to become the President & C.E.O. of the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation, and David Landsberg, whose entire career had been at the Herald, was named publisher. By then the Herald was feeling the effects of declining subscribership and advertising revenue. In July 2006 Knight Ridder was sold to The McClatchy Company for $4 Billion in cash and stock, and assuming $2 Billion in Knight-Ridder debt.

The Landsberg era was busy, both for the Herald and for groundbreaking news. In Washington, the Democrats took control of both houses of Congress, and Nancy Pelosi becoming the first female Speaker of the House. The financial outlook of the country was grim, with a recession beginning in December 2007, and a global financial crisis when the stock market crashed. History was made when Barak Obama was elected the first black President, and a rock era ended in 2009 when Michael Jackson died, prompting the largest display of public mourning for a celebrity since the death of Elvis Pressley. There was no mourning when Osama bin Laden, who led the September 11, 2001 attacks, was tracked down and killed by U.S. Navy Seals in 2011. It had been a ten-year manhunt.

In 2013, a Malaysian Company offered the Miami Herald Media Company $236 Billion for their building, a landmark set on 14 acres on Biscayne Bay. With technology moving at warp speed, it was deemed that being in the heart of the city was no longer a necessity. The offer was accepted, and the Herald moved to new headquarters in Doral. The building was demolished in April 2014, symbolically ending an era for the Herald.

When Landsberg left the newspaper industry in 2014. Alexandra Villoch, with the Herald since 2000, became its first female publisher. Noting that all businesses will at some point go through a transformation process, she noted that the newspaper business was no different. A key element to the transformation was maximizing use of digital delivery. She noted that the Herald’s websites, apps and digital products had reached nearly 9 million users. Her promotion meant that Hispanic females, herself and two executive officers, now occupied three key positions at the paper.

Two of several big stories that took place while Villoch was publisher were when same-sex marriages were legalized in all 50 states in 2015, and when Donald Trump was elected President in 2017. During her time as publisher, as the newspaper industry continued to evolve and change, Villach’s team continued to earn professional recognition, as demonstrated by the several Pulitzers awarded to the Herald under her guidance. Villoch resigned in April 2019 to join the Baptist Health Foundation.

Her successor, Aminda Marques Gonzales became the second Hispanic woman to become Publisher, and since 2019 major stories have been frequent. In July, President Trump was awarded $2.5 Billion to build his much debated Mexican wall, in August, financier and sex-tracker Jeffery Epstein was found dead in his jail cell, the U.S. House impeached President Trump in December, the coronavirus outbreak began in the United States in January 2020, and Trump was acquitted in February. Marques has had a busy first year as publisher.

1 HERALD PLAZA

Miami’s Front Porch

Before its construction, Herald facilities were far from glamourous. The paper’s first headquarters was located in downtown on Miami ave and was an unassuming, dusty storefront. When business picked up, the Herald purchased and repurposed the building behind it to expand printing capabilities. Growth in circulation in the years that followed would continue to demand larger and larger facilities from the paper. In 1940 a new, more upscale downtown headquarters was built in streamline moderne style to keep up with increasing demand. The ashes of Frank Stoneman, founder of the newspaper, were poured into a concrete column in the newsroom during the building’s construction. While the headquarters reaked of liquor and offered no privacy, it was fondly remembered by employees.

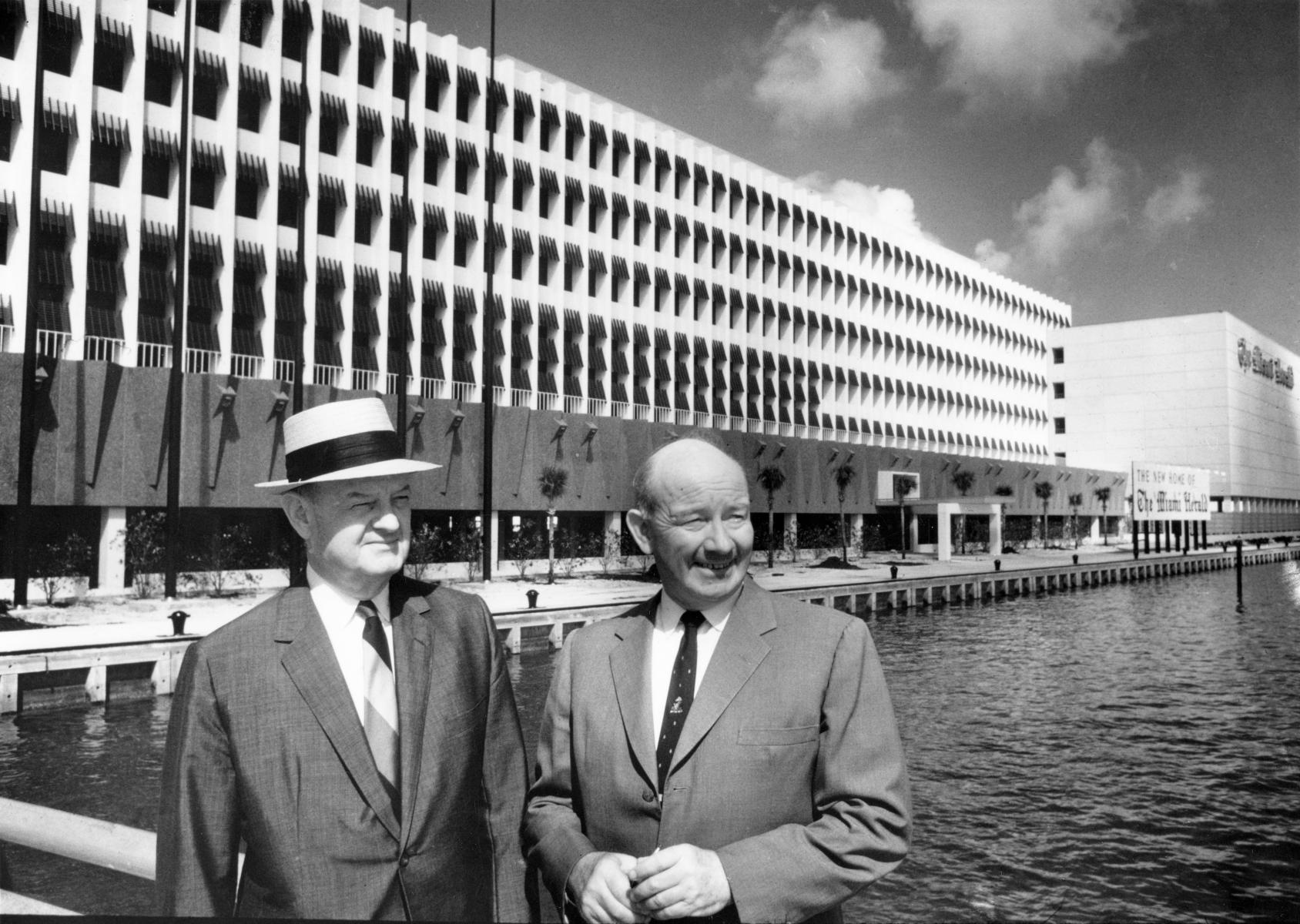

By the 1950’s there were no signs that circulation growth was slowing down and it became clear that expansion would once again be required. Plans were drafted to purchase the building adjacent to its headquarters in Downtown Miami but were ultimately due to an exiled Cuban politician purchasing the building before them. James Knight, who was much more involved in the day-to-day operations than his brother was, took up the torch, turned his eyes to glimmering Biscayne Bay and dreamt of the beautiful newspaper building he would soon gift to Miami. Once Knight decided on the area between the McArthur and Venetian causeways, a plan was set in motion to acquire the land.

The site had previously been occupied by various night clubs that had been of immense popularity during the war and were demolished soon after. Just before the Herald purchased property, it was being used to display giant, neon-lit billboards whose lights would reflect onto the bay and would catch the eye of commuters going to and from the beach – It had been referred to as the Times Square of Miami.

After 7 years of secretly acquiring and consolidating 10 acres of property between the causeways, Knight convinced acclaimed architect Sigurd Naess to forgo retirement to design the building-to-be. Danish-born Naess had previously designed the acclaimd Chicago Daily News and Sun-Times buildings. Knight worked closely with Naess and an engineering firm calculate and predict the newspapers circulation in 1980 so that the building could be constructed to accommodate necessary growth over the following two decades. It was determined that the Herald would reach circulation of over a million by 1980 and would need to build accordingly.

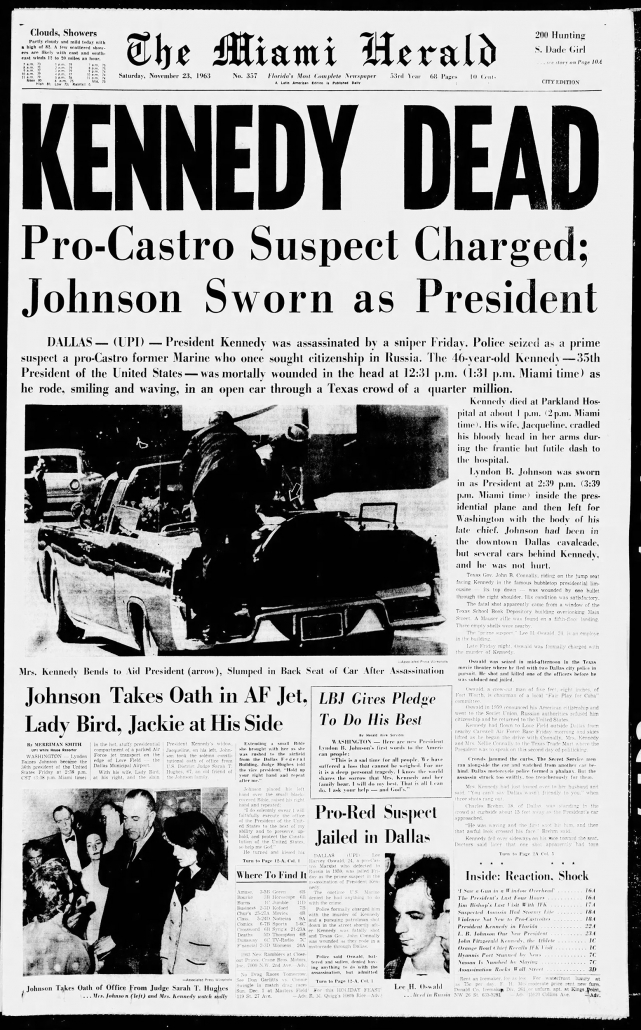

Once plans were completed and John Knight was convinced by his brother that this ambitious, $30 million-dollar plant would not “do them in,” ground was broken on August 19,1960. After 3 years of construction, the Miami Herald Building opened its doors on _____ 1963 to over 10,000 guests for a tour of the building. Congratulatory letters and telegrams were sent by luminaries from across the nation, including President Kennedy , President Eisenhower, and countless others.

1 Herald Plaza was the largest building in Florida when completed and perhaps one of the grandest examples of subtopic modernism in the entire United States. It was essentially two structures sewn togther – an office building and a printing plant. Its modernist design was shaped by South Florida’s unique climate, demonstrated by its sun grills, eggcrate façade, and subtropic color palletes. The building’s main body was raised up one story to protect against flooding from the bay in the event of the hurricane. It featured external expressions of internal functions – a hallmark in the modernist movement sweeping the nation during the 1950’s and 1960’s.

The lobby was defined by grand, double-height ceilings and featured escalators which would lead to the second-floor business office, another expansive, double height-space with sweeping views of Biscayne Bay and Miami Beach. The press building, which was both massive and windowless, was situated at the north end of the structure. Many of the print machines from the old plant were disposed of in favor of some of the most cutting-edge print technology available at the time. A specifically designed airspace kept the vibration of the presses from interfering with office work and like other newspaper buildings Naess designed, the Herald building received paper for printing via barge.

The building sat at the hub of Miami’s wheel for over five decades and, following national trends which situated printing presses outside of the city’s center, the Miami Herald moved its headquarters and facilities to Doral. The site on which 1 Herald Plaza occupied sits vacant to this day, with no clear indication as to what its future holds.

One Herald Plaza, 1963.

Presented by: